Art, Death, and the Museum

June 20th, 2009The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is one of those designs contentious enough to split adherents and detractors right down the middle. Mario Botta, the museum’s architect, assembled his design from a palette of archetypal elements he arranges into a desired effect. The forms aren’t symbolic in that they mean anything, but they do convey general themes.

At the SFMoMA for example, the composition intimates sanctity, rootedness, exclusion from the outside, attention toward sun and sky, and so forth. This is done with a skylit cylinder set atop a nearly windowless, square masonry base, sheltering a broad opening of an entry. The masses hunch in a vaguely animorphic way, gazing over the recumbant postures of the Center for the Arts buildings across the street.

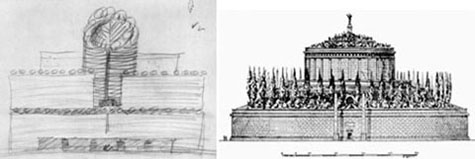

In his original proposal however, Botta’s ensemble was to be crowned with a ring of ficus trees planted atop the cylinder. This feature, almost unseen in the history of architecture, did figure prominently in the mausoleum of the ancient Roman emperor Augustus. Though only ruins of the mausoleum remain today, scholarly reconstructions all show an earthen mound over a windowless masonry cylinder and square base, planted with a great ring of oak or laurel trees.

Trees as seen on the SFMoMA and a reconstruction of the Mausoleum of Augustus.

Was the allusion to a mausoleum intentional? Was Botta making a subtle poke at the state of the art collection? And why is it that art should be so easily housed within such a tomb-like structure?

I’m comfortable arguing against the poke. Botta studied under Carlo Scarpa, and went on to work for le Corbusier and Louis Kahn. Common to all three was a predeliction for the primordial origins of form. The shapes a building assumes come from something deep rooted. There is something archetypal in the masses of many of these architects’ buildings – something so common to our collective conscious that we may intuit what a building is about even before we know what’s inside. And the deep roots that sprouted the basic form of the mausoleum may easily have brought forth the basic form of this museum.

Given how distanced from everyday life art seems when experienced in the sanctum of a museum, it shouldn’t be surprising that the forms of museums occasionally bear some relation to those of mausolea. The raised earthen mound of Augustus’ mausoleum lifts up the image of burial as if foisting upon us how removed from us it is. The museum similarly enshrouds its contents on a pedestal. Historically museums have made no pretense about this, and examples in San Francisco are not new.

The Egyptian revival de Young of 1894.

The original de Young Museum, of the 1894 Mid-Winter’s Fair in Golden Gate Park, was designed in the tomb-like Egyptian revival style. Two of the original sphinx remain, and have been reinstalled outside the new building. It was not an uncommon style for museums, with its intimations of preservation and eternity.

After the original building was damaged in the 1906 quake, a reconstructed edifice continued the same theme. Though not overtly Egyptian revival, the central tower with its nearly-pyramidal roof form bore a notable resemblance to the original Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the so-called ancient wonders.

The post-quake de Young, and the original Mausoleum at Halicarnassus.

The latest de Young building eschews the burial analogy. The architects, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, did consider sodding the roof early on. But despite the current trend toward green roofs, they wound up dropping the idea, feeling it inappropriate to showcase arts under an earthen roof. (The irony here is that the de Young houses some of the most moribund art in the city – the Oceanic and African relics long removed from the vitality of their accompanying rituals.)

But what is it about art and death that moves us to inter them so?

“The animus of the museum is to value the plucked fruit more than the tree that bore it.” – Lewis Mumford

Art dies, in a way, when hung in a museum. Its relation to the outside world is muffled. Its meaning within, and allusions to its original melieu are severed. Influence is assimilated, and the impact of the art fades. This is why one wears black to openings.

There are of course works of art that don’t require context (paradoxically, one has to know this to best appreciate them), or that rely on the blank white walls of the museum for effect. But museums can drain vitality from art in other ways. The mere presence of a work in a prominent museum can legitimize it in the public mind. When an artist’s work is represented in a museum’s collection and sanctified in catalogs, it runs the risk of being canonized – studied dutifully by the next generation of art students. Each new wave of the avant-garde loses its impact this way.

But in “death”, art may gain something. On hearing of a collegue’s passing, our thoughts may turn toward their legacy, how they impacted us or our community. Their vitality is taken from us, and not until its absence do we appreciate it most keenly.

This is the impetus behind mausoleum design. There is something worth preserving here; there is something worth remembering. This is not architecture of the living; this is the architecture of remembrance. And this is the innuendo in Botta’s design.

September 17th, 2009 at 5:29 pm

Terrific essay. Why do you think of museums as essentially separate from everyday life? The hushed interiors of most museums closely resemble a number of other spaces: churches, late-night supermarkets, schools, subway stations. It’s too easy to define what’s everyday as what’s not museal. And when art’s well hung, it can do better in a museum than anywhere else. Where would you put a Richard Serra? Your sun room?

November 23rd, 2009 at 2:46 pm

Just came across this – guess I’m not alone in recognizing the analogy:

“Collections have always had overtones of burial and interment…. The greater a collection, the more precious its contents, the more it must be reminiscent of a mausoleum, left behind by a ruler determined not to be forgotten…”

— Philipp Blom, from To Have and to Hold: an Intimate History of Collectors and Collecting

March 19th, 2012 at 2:01 pm

[…] might also draw a link to Boulee’s monument to Newton, in my exploring the roots of Mario Botta’s SFMoMA. This time a spherical top over a windowless cylindrical base, and again, rings of Cypress trees. […]

October 26th, 2021 at 8:48 am

Visakhapatnam is a port city and industrial center in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, on the Bay of Bengal. It’s known for its many beaches, including Ramakrishna Beach, home to a preserved submarine at the Kursura Submarine Museum. Nearby are the elaborate Kali Temple and the Visakha Museum, an old Dutch bungalow housing local maritime and historical exhibits.

Visakhapat

Visakhapatnam is a port city and industrial center in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, on the Bay of Bengal. It’s known for its many beaches, including Ramakrishna Beach, home to a preserved submarine at the Kursura Submarine Museum. Nearby are the elaborate Kali Temple and the Visakha Museum, an old Dutch bungalow housing local maritime and historical exhibits.

November 19th, 2021 at 5:06 pm

Hoch Und Deutschmeisterkapelle 45 Touren Sonderklasse https://steamcommunity.promalp.biz/13.html Reggie Stepper Mary Button

January 23rd, 2022 at 4:56 pm

Построить дом можно и своими руками. Но, сказать по правде – это не будет очень быстро, тем более, если у вас нет достаточного опыта. Ввиду отсутствия опыта дом будет строится медленно и возможно допущение определенных ошибок. Лучше доверить строительство профессионалам.

September 4th, 2024 at 4:28 am

Официальный сайт букмекерской конторы олимпбет – удобная платформа для ставок на спорт и киберспорт с широкой линейкой событий и высокими коэффициентами